Fruit market in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Antonio Salaverry/Shutterstock

While there is more than enough food produced to feed the world’s population, hunger and food insecurity persist.

In 2024, around 8% of people faced hunger, while about 28% were food insecure (without consistent access to safe and nutritious food).Global supply chains are important for feeding and nourishing people around the world.

In this vein, the World Bank funds projects that facilitate trade in food and trade of agricultural inputs such as agro-chemicals, both within and between countries and regions.

But my research shows how wealth and poverty are two sides of the same coin. Wealth and poverty can both result from the growth of convoluted and globalised food supply chains. While such supply chains can reward large-scale exporters of relatively high value products, they can undermine local food systems.

As export volumes increase, the expansion of food sectors into global supply chains actually reduces food security in significant ways. Conversely, establishing the right to food domestically represents a viable way to combat food insecurity.

Read more:

How to reduce the hidden environmental costs of supply chains

Brazil highlights how both issues play out. Despite being a major world food producer, food insecurity, and often hunger, in Brazil have been long-standing problems.

Following the election of the Workers’ Party in 2002, a decade of pro-poor policy – including the flagship fome zero (no hunger initiative), bolsa família (the family allowance grant) and rising minimum wages – reduced hunger and food insecurity. The country was removed from the Food and Agriculture Organization’s world hunger map in 2014.

However, Brazil was returned to the map in 2022 following COVID pandemic price spikes and the Bolsonaro government’s abandonment of much of the previous pro-poor policy agenda. Then, following the victory of the Workers’ Party in 2022, the reinstatement of pro-poor policies and consequent falls in levels of hunger, it was taken off the map again in 2025.

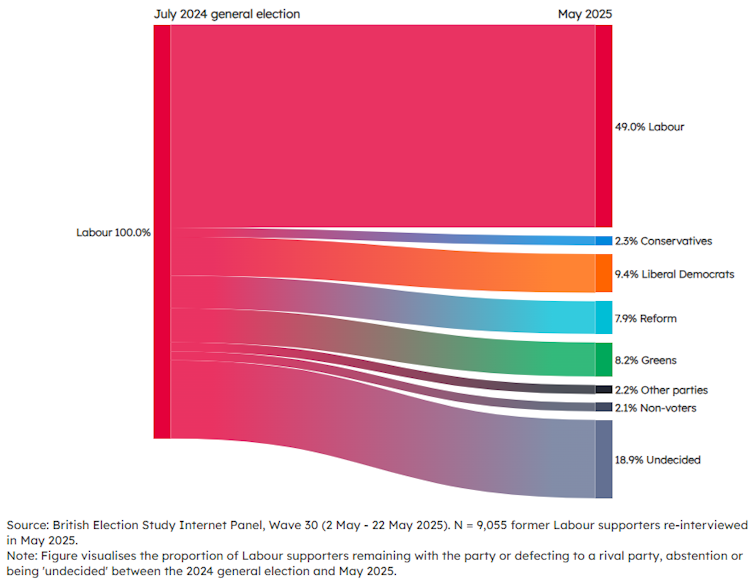

Brazil accounts for more than half of the world’s soybean trade.

Alf Ribeiro/Shutterstock

This recent removal is good news, but food insecurity still stalks the country where 28 million Brazilians – predominantly women and children – still face food insecurity.

While social policy influences rates of food insecurity, so too do agricultural systems. This is where the differences between integration into high value global supply chains and attempts to formulate alternative food networks becomes apparent.

Brazil used to have a relatively diversified national economy. Since the 1990s, under governments of different political stripes, its integration into global supply chains has occurred through exporting a few primary products.

Brazil accounts for more than half of the world’s soybean trade. About 70% of that goes to China for use as animal feed. It is also the world’s second largest corn exporter, mostly for animal feed and biofuels.

Such exports have enriched Brazilian agribusiness, but they have undermined domestic food production. This is negatively affecting the food security of poorer communities. Between 2010 and 2022, soybean production increased by over 100% while rice production fell by 30%. The production of other basic food crops also fell.

Domestic food prices increased faster than general inflation, and low-income families have experienced food insecurity and have cut their food consumption.

The struggle for an alternative

But there are alternatives to this model. In 1993, the newly elected Workers’ Party mayoralty of Belo Horizonte declared the right to food for its 2.5 million population, and the city government’s duty to guarantee it. Its success influenced the formation of the national fome zero programme in the early 2000s.

Since then, with some variations depending on the party in power, the city mayoralty has dedicated 1-2% of its annual budget – less than US$10 million (£7.7 million) per year – to the scheme.

Long-term effects include a 25% reduction of people living in poverty, a marked increase in consumption of fruit and vegetables among the poor, and 75% fewer children under five being hospitalised for malnutrition than prior to the scheme.

The system encompasses production, distribution, and consumption. The local government’s Secretariat of Food Policy overseas and is responsible for implementing the right to food across the city. It facilitates local participation by small farmers and businesses, workers and consumers.

Objectives included using the city government’s purchasing power to stimulate local, agroecological food production, linked to consumers in ways that reduce prices while maintaining small farmer’s incomes.

Public restaurants, open to all, provide 20,000 healthy meals a day – organised by local chefs and nutritionists – for less than US$1 dollar per meal. Lunch (Brazilian’s main meal of the day) typically consists of rice, beans, meat, salads, fruit and juice.

Under the scheme meals from public restaurants are sold at cost price – the cost of food production, distribution and maintaining restaurants. Registered homeless people eat for free, and beneficiaries of the bolsa familia scheme get a 50% discount. Another 40 million meals are served to over 150,000 students a year under the scheme’s school meals programme. The city government partners with selected groceries to sell a range of products, often sourced locally, at 25% below market prices.

Under the scheme’s “straight from the field” programme, the city purchases food directly from producers for its public restaurants. The city provides inputs to low-income farmers and empowers them with secure land tenure. Local and regional family farms are encouraged to produce basic and other food crops for sale in the city through farmers and traditional markets.

Read more:

The right to food: activism and litigation are shifting the dial in South Africa

Global supply chains are designed and operate as systems of production and trade that reward profitable exports, rather than combatting food insecurity. They often direct resources away from where they are needed to where they are profitable.

When right-to-food systems are established to tackle food insecurity, as in Belo Horizonte, they must cater to their local context. Policies such as subsidised food consumption and production, plus coordinated distribution are all ingredients required for tackling food insecurity.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Benjamin Selwyn does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.